02/12/1962 • 55 views

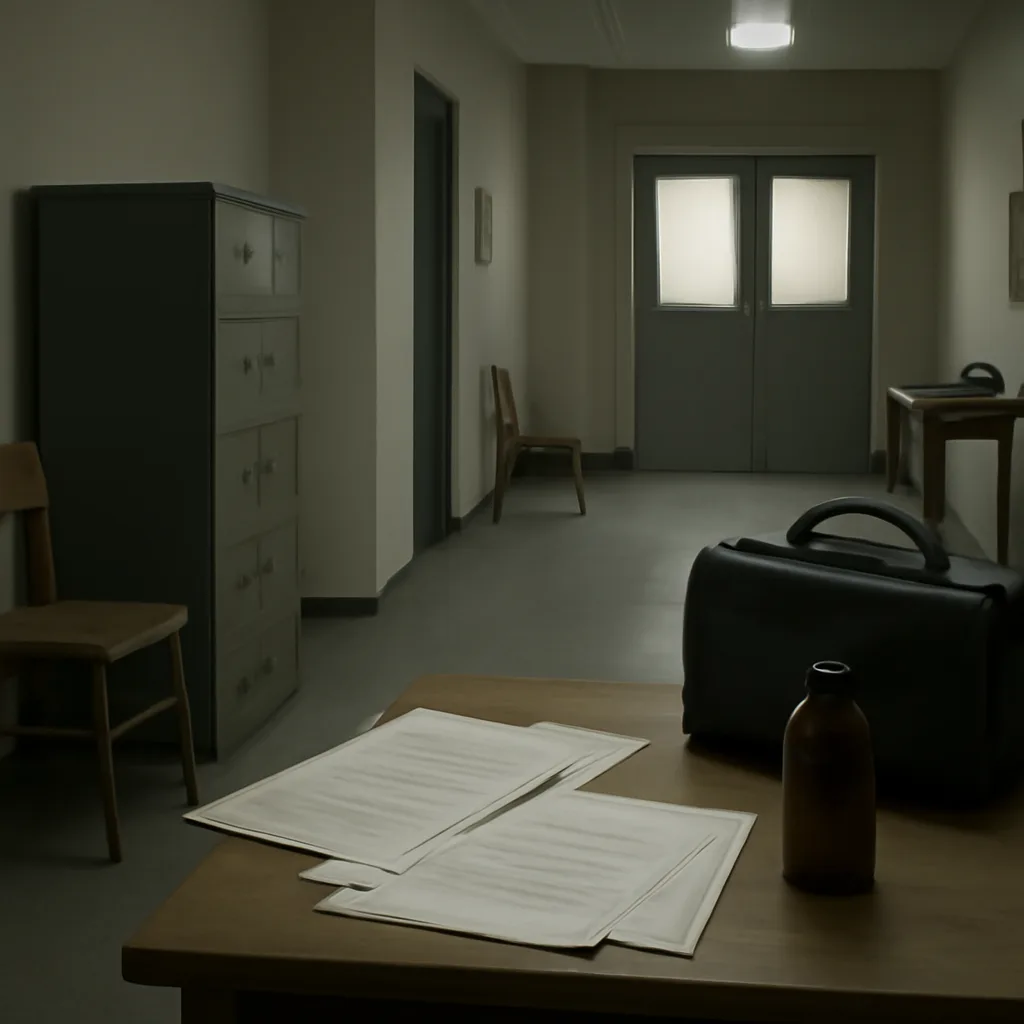

FDA Withdraws Thalidomide After Link to Birth Defects Emerges

On Feb. 12, 1962, amid mounting evidence that thalidomide caused severe limb deformities in newborns abroad, U.S. regulators moved to block its approval and distribution, marking a pivotal moment in drug safety oversight.