03/17/1933 • 38 views

1933: The first documented deaths tied to a prescription weight-loss drug

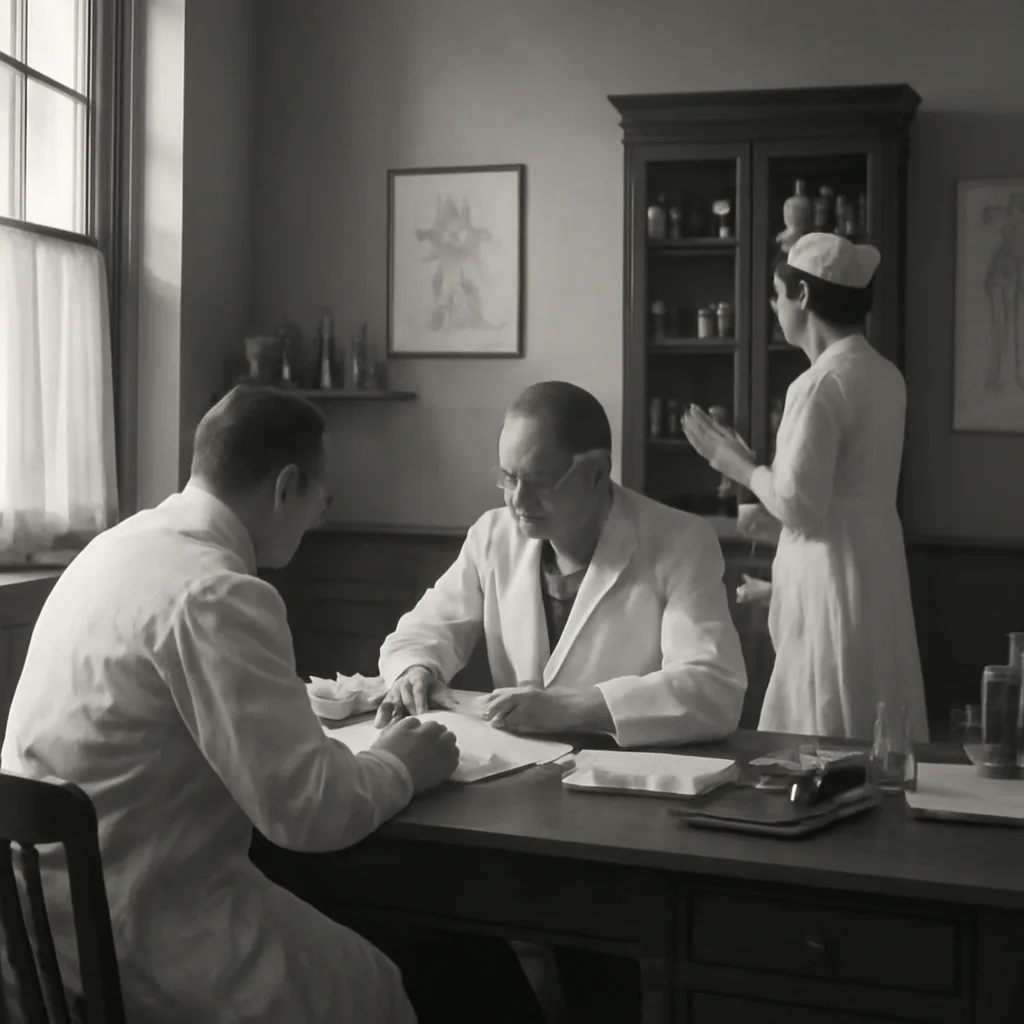

On March 17, 1933, physicians linked fatalities to a prescribed weight-loss medication—one of the earliest documented cases showing that slimming drugs could carry lethal risks, prompting scrutiny of pharmacological approaches to obesity.