02/06/1978 • 47 views

CIA Acknowledges Use of 'Truth Serums' in Past Interrogations

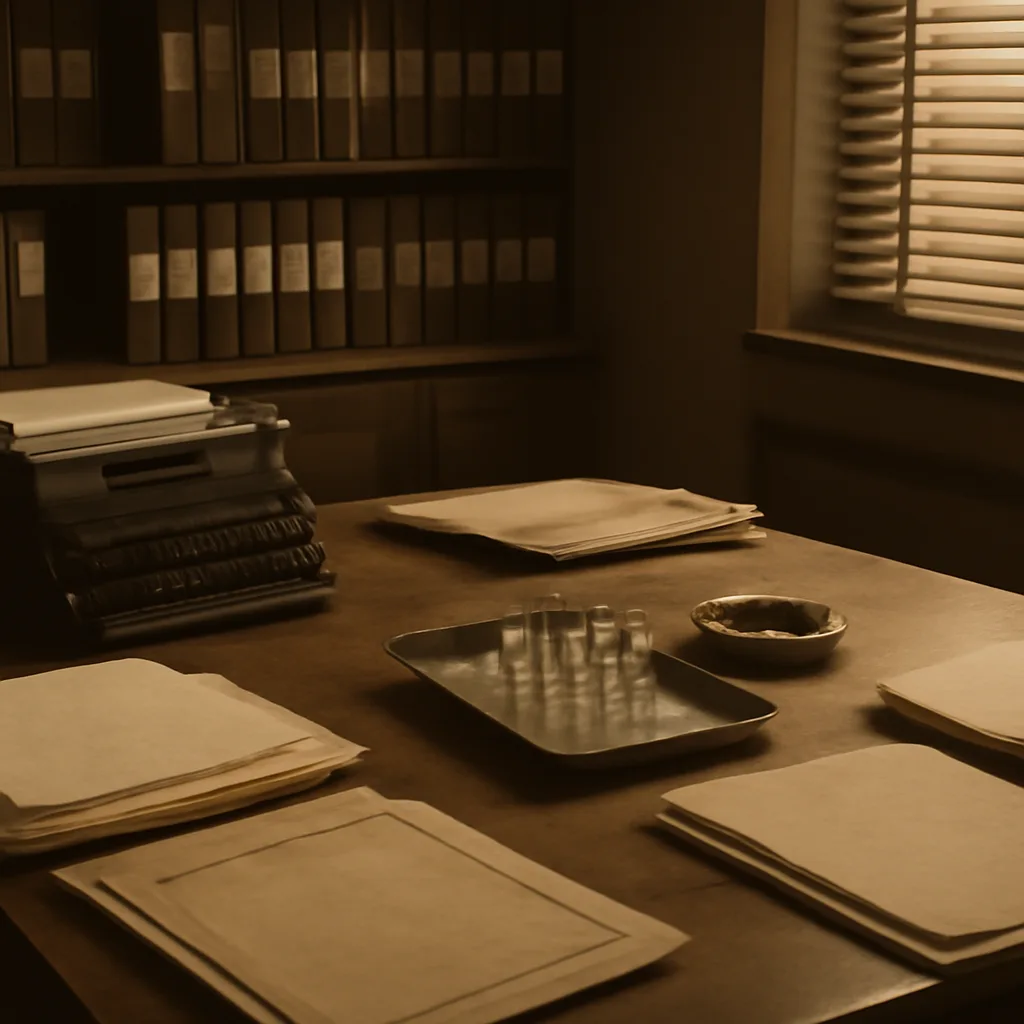

In a Feb. 6, 1978 disclosure, U.S. authorities confirmed the Central Intelligence Agency experimented with so-called 'truth serums' during Cold War-era programs; officials said such substances were tested but cautioned about their reliability and ethical problems.