02/15/1975 • 43 views

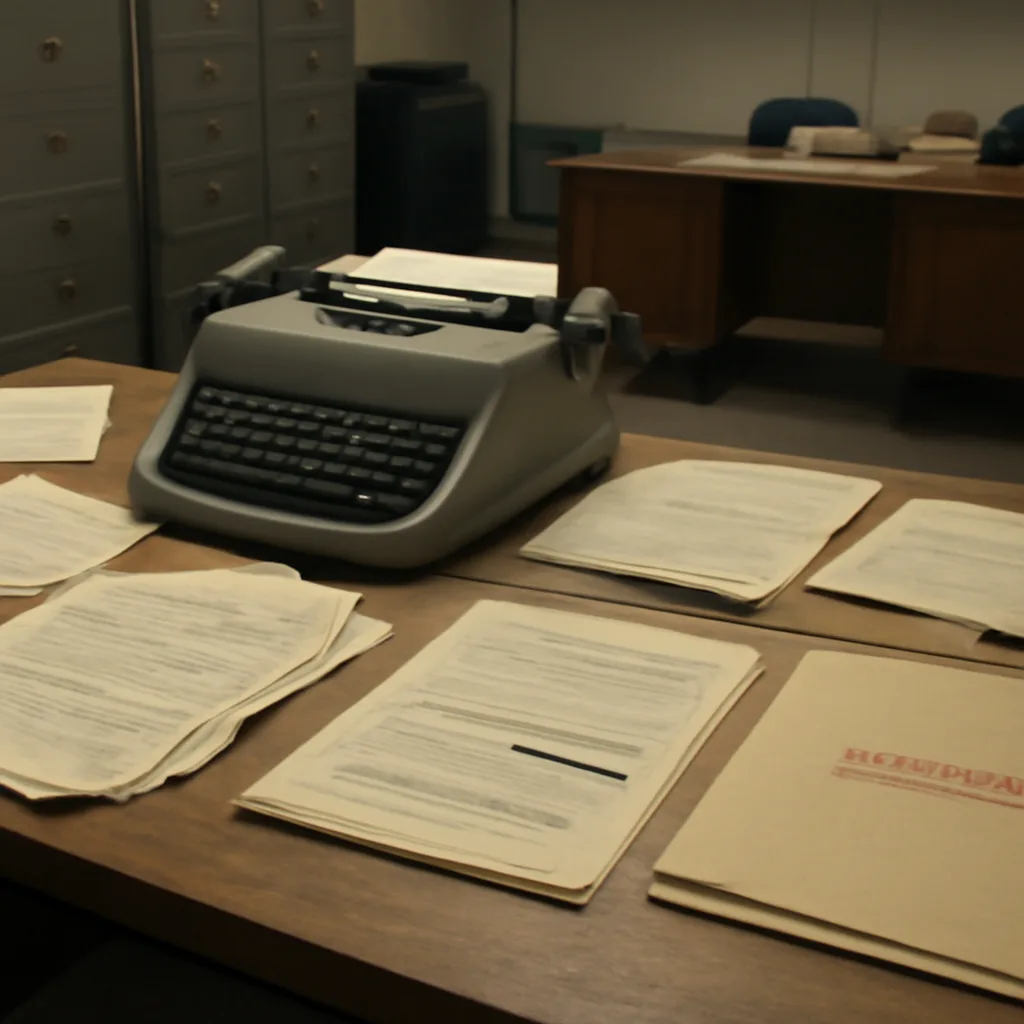

CIA Declassifies Files on Cold War Mind-Control Research

On February 15, 1975, the CIA disclosed documents revealing government-funded experiments into behavior modification and interrogation techniques—sparking public debate over ethics, oversight and the limits of intelligence research.