05/09/1961 • 49 views

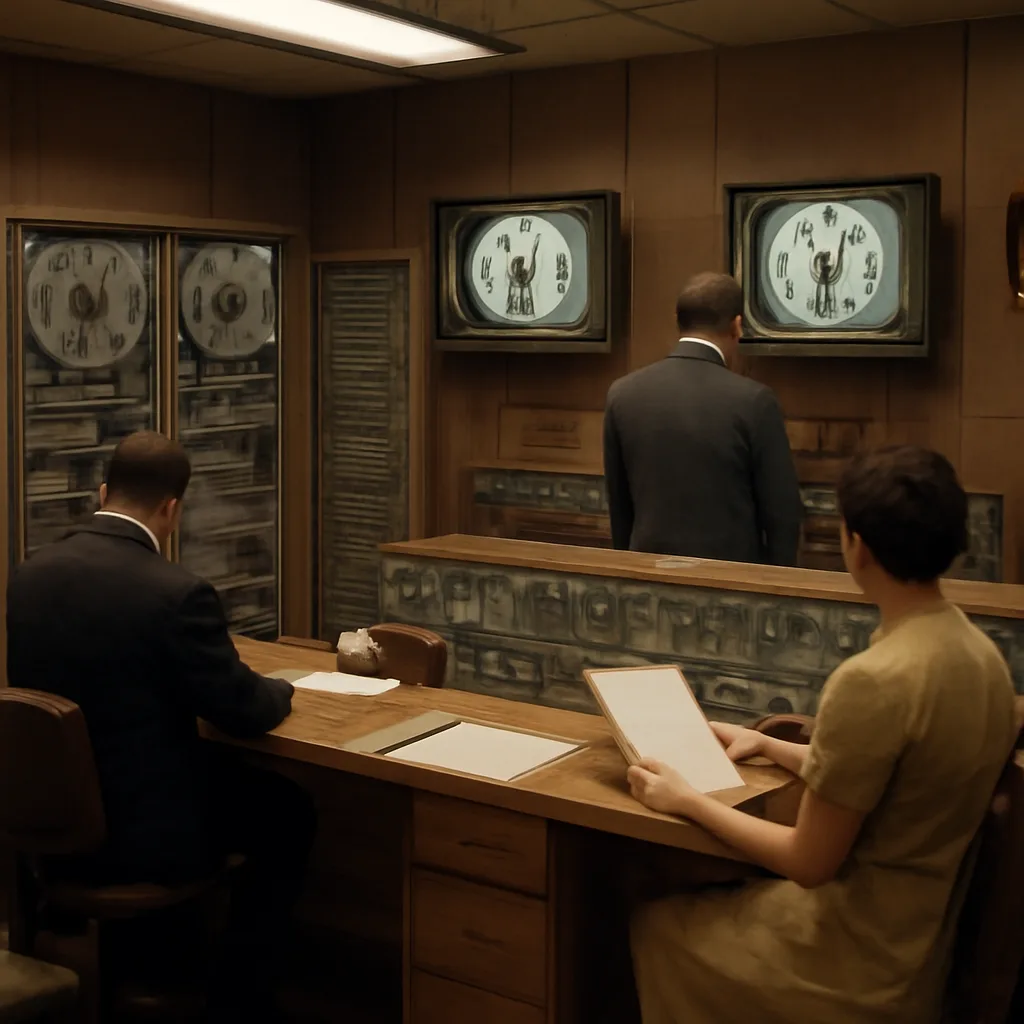

First National Emergency Broadcast Test Sounds Over U.S. Airwaves

On May 9, 1961, the United States conducted its first nationwide test of a modern Emergency Broadcast System, sending standardized alert tones and messages over radio and television to evaluate readiness for national civil defense communications.